Christine Crozat has counted among the key artists in the Musée Réattu’s contemporary collection since her solo exhibition there in 2002. Her both sensitive and memory-based approach to the history of art, that she revisits through drawing, sculpture, photography and video, strikes a strong chord with this museum of fine arts continuing a dialogue between its old collections and the most contemporary forms of visual art. The museum has a substantial collection of her works, to this day eleven drawings and three sculptures. Christine Crozat’s artistic practice draws comparison with Japanese haiku with her economy of means, simple materials and techniques, the way in which her compositions are pared down, transposed to the world of poetry. This comparison is significant as Japan has a special place at the heart of her intellectual and artistic culture. Her love of this country with its landscapes, philosophy and aesthetics, along with her relationship with poetry of the everyday has been embodied in recent years in videos produced over the course of her travels throughout the archipelago, in collaboration with the writer Pierre Thomé.

In Amanohashidate, literally ‘bridge in heaven’, she focuses on one of the three most famous views in Japan. It is a narrow strip of land dividing Miyazu Bay into two, where there is a centuries old tradition of taking in the view from Kasamatsu Park from where visitors admire the landscape by lowering their heads between their legs to invert the ground and sky. The artist features this poetic and burlesque practice here in the form of a performance: lying on a bench in front of the view, her feet clad in tabi raised upwards to the sky. Suspended, she begins a slow walk along the tombolo. Pierre Thomé films the scene upside down too, further disrupting the benchmarks of this landscape that has been represented and photographed time and again.

She prepared the exhibition Mine de rien, held at the Musée Réattu in 2002 by roaming the streets of Arles. She mainly covers the Musée Réattu’s permanent collections, where she discovered the Arlesian traditional outfit through Antoine Raspal’s realistic depictions, as well as through Picasso’s deforming prism. Ten drawings according to Raspal and Picasso therefore came to fruition. Five of them were purchased by the museum at the end of the exhibition. Aware that these Arlesian headdresses have significant resonance in the place in which they originated, the artist wished to offer the five remaining drawings of Coiffes – three according to Raspal, two according to Picasso –,that complement the set of works produced in Arles in 2002.

Over the course of the retrospective exhibition dedicated to Véronique Ellena in 2018, it became apparent that the museum had to future-proof the relationship developed with the artist who had already carved a name for herself in Arles since the exhibition ‘Musée Réattu, Christian Lacroix’ ten years previously. That is why five photographs from the Clairs-Obscurs serieswere acquired in 2018 for the photography department, to which was added La Vigne du Clos, a photographic stained-glass window designed for the architectural volumes of the Grand Priory, that the artist and master glassmaker Pierre-Alain Parot logically decided to offer to the museum. Now, a private collector, with works on loan to the exhibition, wishes to donate a photograph from one of Véronique Ellena’s most emblematic series: Les Natures mortes. Created at Villa Médicis, where the photographer was a resident between 2007 and 2008, the Natures mortes series fully embraces the complicity that her images have always enjoyed with painting. The photographer thereby produces frontal images that are monumental yet intimate, establishing proximity between the viewer and the object. The textures are rendered with the same sensuality as the impasto and glazes of oil paintings. La grenade is one of those images that is so lucid and rich that its presence is disturbing, blurring the boundary that separates painting from photography.

Patricia de Gorostarzu became a self-taught photographer at the age of 14. It became her profession from 1985, behind the scenes in laboratories developing and printing photographs by other photographers to begin with, then as a photographer in her own right from 1990. She began with commercial photography and worked with the music press and various record labels, producing reportages and portraits of artists.

In 2003, after crossing the United States, she decided to publish her first photo book, D’Est en Ouest, which heralded an extensive list of publications, books playing a large role for her in circulating her photos. In 2006, Galerie Agathe Gaillard began to represent her, confirming the increasingly artistic leaning of her photographic practice. It was during this period that she began to think about the distance that exists between an image that is intrinsically reproducible – from the negative or digitally, in the case of Polaroids for example – and the medium, one that is often unique with her work. She has since taken the decision to no longer reproduce her shots, solely exhibiting and proposing her original Polaroids for acquisition.

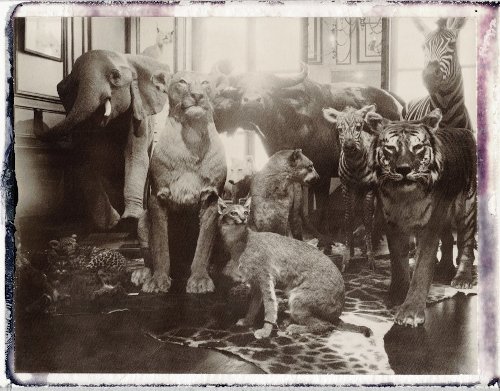

The artist’s work is fuelled by her travels. The most symbolic series in this respect, D'Est en Ouest follows the legendary Route 66. Between landscapes and portraits, the series pays tribute to leading photographers who portrayed American society post the Great Depression, like Dorothea Lange and later Robert Frank. Use of a Sinar 20 x 25 camera and a Polaroid 20 x 25 developer enabled her to achieve these sepia shots in faded tones, the melancholy of which softens the weathered faces and landscapes scorched by the sun, a memory of which she wishes to keep alive. The USA Polaroids recall American experiments with colour photography in the 1960s. Inspired by photographers like William Eggleston and Stephen Shore, this is a more graphic series, playing on details of urban landscapes forming a substantial part of popular American iconography. Use of a Polaroid camera dated 1962 blurs the temporality of the images and gives them a vintage appearance consistent with her quest for authentic shots. The Paris series is part of the great tradition of French humanistic photography and the principle of ‘objective chance’ a method established by Surrealist photographers, adopting their favourite themes: shop windows, mannequins and stuffed animals. She also pays tribute to photographers of the New Objectivity movement focussing on symbolic architecture that she photographs with a great deal of high and low-angle shots, diagonals and graphic details. Here again, the diluted colours and contrasts in the sepia blurs the tracks and the subjects photographed alone enable the images to be dated.

A dual objective connected to memory can be distinguished in her work: the memory of the places that she photographs, often charged with the memory of leading photographers, and that of photographic techniques from the past, that she reactivates by using traditional cameras, replacing the original shot at the forefront of her production and reintroducing slowness into the process of taking a shot (up to forty minutes for certain images).

After donating several works to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and integrating the Maison Européenne de la Photographie collections, Patricia de Gorostarzu decided to offer the Musée Réattu a selection of original and unique copies to ensure their preservation.

Suzanne Hetzel, a German artist who has lived in Arles for several years, is one of those artists from the north who was attracted to the southern light and never left. An important aspect of her work lies in collection. The idea of collection and the gestures of collectors play a crucial role in the eye of the artist: containing the flow of our memory and providing a context for the past, present and future. Whether found in the street or walking in the countryside, the objects then feature in photographs and installations that highlight their aesthetical qualities and accompany the autobiographical narratives that the artist concurrently drafts.

For the Ailes series she collected wings and feathers from various animal species present in the Camargue or that she bought from taxidermists in the guise of an entomologist, or an ornithologist. These objects assembled like an herbarium, were then photographed to display their fragile beauty. To render textures and colours more authentically, the artist selected a more unusual process, a scanner rather than a camera. The clinical rendering created by the digital scanner gives these wings a disturbing presence that echoes the artist’s installation work: display cases with illuminated backgrounds. This permanent back and forth between the object and its image –not just a simple representation, but a two dimensional double–, between nature as it is and its transposition into a work of art, resonating with the museum it makes the collection intriguing. Use of the scanner aligns Suzanne Hetzel with Katerina Jebb, an English artist who has virtually exclusively made it her medium. Sensitive to the wealth of the natural and cultural heritage of the Arles region, Suzanne Hetzel has developed a body of work rooted in the notion of identity, examining the inner workings of affiliation to this region and the traditions that animate it. The question of appearances becomes central when pieces of clothing are involved. Clothing is thereby seen as an envelope, a membrane, reflecting, filtering and deforming what is contained within. The artwork given to the Musée Réattu, Habit de lumière, is a part of this process and presented in the shape of an installation combining photography and objects.

The photograph was taken during an interview with the bullfighter Juan Bautista in Camargue. The light that passes through the living room illuminates the gold trimmings of the suit worn just once by the matador during an Easter bullfight in 2015 in the Arènes d'Arles. Beyond a simple robe of honour, the costume of light is a for the bullfighter a sort of metamorphosis, a temporary envelope that he will no longer wear but that accompanied an important stage in his career. A symbol of prestige, it is a symbolic envelope that embodies the qualities expected of a matador: courage, dignity and virility, maintenance of tradition. The artist has chosen to combine the unadulterated image of this clothing, placed on the edge of the sofa without being staged, with a tin of beetles bought from a taxidermist: chrysina plusiotis resplendens, the exoskeletons of which are exceptionally glossy and have an incomparable golden hue. Colour, regarding insects, is connected to their place in the ecosystem, it forms a visual language that other species must interpret, like the colours and embroidery of the matador’s suit, the codes of which will be decoded by supporters.

By bringing together two worlds – that of people and animals, image and object – Suzanne Heztel creates a poetic shift drawing viewers into a reflection on people and appearances, about the role of the envelope – clothing, exoskeletons, plumage, etc. – for conveying identities.

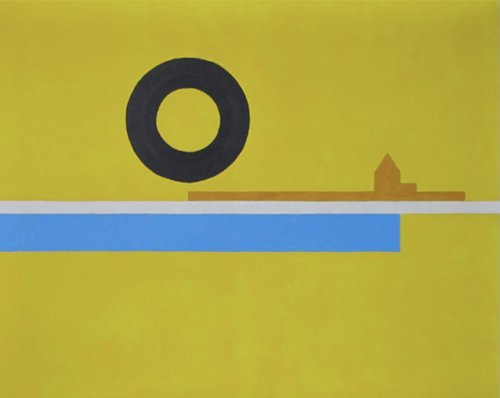

The son of a typesetter from the Imprimerie nationale, Alfred Latour was interested in drawing at an early age, becoming particularly skilled. He was soon gained recognition among his peers and won several awards throughout his career. His career took off in Paris in the 1910s. Taught at the École des arts décoratifs, after a brief stint at the Ecole des Beaux-arts, he acquired an eagle eye and solid artistic vocabulary giving him an aptitude for graphic design and fashion design, as well as advertising and photography. Joining the Union des artistes modernes in 1935 as a ‘graphic designer’, he excelled in visual communication, developing among other things, at the time, advertising images for Vins Nicolas. He also worked in bookbinding, illustrating many publications in pen and with prints that became sought-after collectibles. From 1929, he worked with the Lyonnais fabric manufacturer Bianchini-Férier developing patterns for haute couture and furniture. Mid-1930s, he produced photographic documentaries for the agency Meurisse in Paris, published regularly in the daily press. Photography, drawing, prints and painting are combined in a continual quest for innovation as the artist sought gateways to make full use of these varying mediums through a range of the forms and supports. Permanently secluded in Eygalières from 1945, Latour tirelessly depicts the landscapes of the Alpilles and the Camargue, in compositions that are increasingly graphic and almost abstract. Examples can be found in the collections of the Centre Pompidou, British Museum, Musée Cantini in Marseille and Musée Ziem in Martigues.

The city of Arles currently has very few works and documents relating to Alfred Latour: one landscape, Collioures (1952), given at the time when his son, Jacques Latour, was curator of the Musée Réattu, as well as graphic pieces for, among others, the Nicolas establishments.

The Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer that the artist’s grandson, Claude Latour, gave to the city of Arles in recognition of the double exhibition that was held at the Espace van Gogh and at the Musée Réattu in 2018, shares the same freedom in the use of colours, discipline in terms of strokes and extreme stylisation of forms with Collioures. This work smoothly integrates the museum collections, presenting other artists alongside Latour– André Marchand, Roger Bezombes and Mario Prassinos – having all, each in their own way, introduced modern art to Provence.

Self-taught photographer Gaspard Noël makes use of his body as the primary material of his photographs. Submerged in huge landscapes that are often distant and willingly extreme – steppes, deserts, glaciers, etc. – he photographs himself in a heroic or rather wild nudity, immediately expelling any question of eroticism or social and cultural affiliation. His productions have titles that are either solemn or ironic (or even comical), attempting above all to interpret his amazement in the face of the immensity of nature. The artist photographs little, as his modus operandi is fastidious. For him photography is above all a question of preparation and endurance: he sets off alone to remote lands and seeks until the point of exhaustion landscapes that are compatible with the visions obsessing him, carrying between 15 and 40 kilos of equipment all day long. Once he finds the right perspective, he places his camera on a tripod, divides the landscape into squares and breaks it down into an average of fifty or so images. He activates the self-timer and enters the field of vision. He then still requires the necessary strength for the shots, that consist most often of climbing the same hill a hundred times, repeatedly diving into the same icy river, or pushing the same rock again and again until a satisfactory result is obtained. Later, when back in civilisation, he reconstructs his photo puzzles on the computer. J'aurais pu naître mouette belongs to a broader series called Présent. Produced in Iceland and printed in large format, the artwork looks like a painting recalling both neoclassical mythological compositions and German romantic painting in the relationship between people and nature that it evokes. This connection with painting also plays with the actual production of the image. It is driven by the photographer’s faultless technique, producing his photographs by means of slow and detailed work reconfiguring the image from many photos. By the end, he comprehensively obtains perfect clarity causing confusion: is the image real? Not quite since this clarity is not actually possible through a camera lens or the human eye. It is therefore a landscape that has been formulated ‘in the studio’, as was the case with painters before the impressionist ‘revolution’. Gaspard Noël exhibited ‘Toucher’ at the Espace van Gogh, from 4th to 12th May 2019, for the 19th Festival Européen de la Photographie de Nu. For the first time, a substantial set of his self-portraits were presented together, complemented by several prints that were produced specifically and notably the one in the donation that the author chose to make to the museum. The relationship between body and landscape, with the idea of the merging of one into the other, is prevalent prevalent in the Musée Réattu photography collection. From Edward Weston’s minimalist nudes produced in the dunes of Oceano to Lucien Clergue’s Venus Anadyomenes, as well as Kishin Shinoyama’s rock-like nudes, analogies between body shapes and those found in nature are far from lacking, at least in terms of the female body, as the male body and its representation is yet to be explored regarding the framework of the photography collection. There is also the almost ‘performative’, at least extremely physical, dimension of Gaspard Noël’s work that interested the museum. The staging of the body in the photographic process, this time found alongside photographers like Arno Rafael Minkkinen – a major artistic reference for Gaspard Noël – and seen in two visual artists reflected in the museum’s photographic and video works: Javier Pérez and Dieter Appelt.